"Boo!": Using Shakeosphere to Scare Up the Origins of a Halloween Refrain

Blaine Greteman

This Friday, October 31, National Public Radio's "All Things Considered" is running a story on the history of the word "boo," and their producers reached out to Shakeosphere for help. The process highlighted several important aspects of our project and the ESTC dataset that I thought were worth addressing. Let's take a look at the tricks Shakeosphere can do and the treats it can offer a researcher – and also some of the spooky surprises that can still waylay the unwary.

First, it is fascinating that Shakeosphere has so quickly become a place where people go to find basic information about historical texts, as opposed to established resources like the English Short Title Catalogue. In this case, NPR producers wanted to learn more about Gilbert Crokatt's Scottish Presbyterian Eloquence Display'd, which the Oxford English Dictionary lists as the first documented source to use the word "Boo" in the way we now do on Halloween. Crokatt ridicules a Scottish minister for using unintentionally hilarious colloquialisms in his sermons, such as "God without Christ is a boo." "Boo is a word," Crokatt adds, "used in the North of Scotland to frighten crying Children."

The OED lists the publication of this tract in 1718, but we were quickly able to see that an earlier version was published in 1692, under the pseudonym Jacob Curate. In fact, as I dug around further in our data and in the EEBO-TCP corpus, I found several other versions of "boo" that might be contenders for an earlier use, and curiously they are all, like The Scottish Presbyterian Eloquence, in the genre of satirical religious polemic. A 1672 poem by the nonconformist Robert Wild ridicules timid Protestants who fear that "The Pope's Raw-head-and-bloody-bones cry Boh Behind the door!" Even earlier, in 1588 the infamous Martin Marprelate – who helped transform English religious polemic from a dry and scholarly affair into a satirical blood sport – ridiculed a Bishop who was too timid to say "bo to a goose." In both the earlier examples, "bo" rhymes with "go," but they are all curiously like our own use of "boo" in their sense of knowing irony – no one is really afraid of the ghost who says "boo," and that is part of the fun. If Crokatt is working in an established tradition, though, the OED rightly identifies his particular use, pronunciation, and association with children as the most direct pipeline to our own trick or treaters, and Shakeosphere helps to clarify why this is the case.

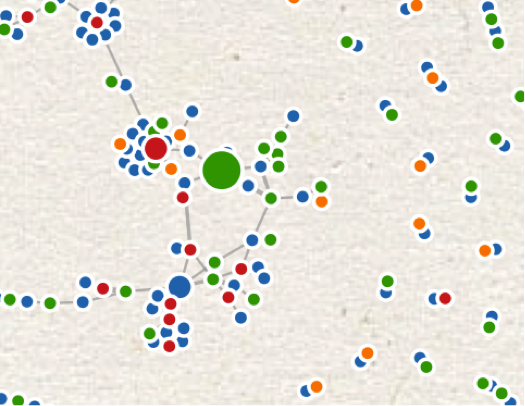

I used Shakeosphere to generate a network map for the 1692. This detail shows the cluster containing the Scottish Presbyterian Eloquence:

What can we learn from this, that we couldn't learn, for example, by searching in the ESTC? I asked Dave Eichmann's student Charisse Madlock-Brown, who is finishing up her PhD in Health Informatics at Iowa, to run some network analytics on this text and see what she found. She started by measuring the degree of "betweenness" of everyone in Crokatt's network. Betweenness is the number of shortest paths from between other nodes that pass through a given node, and in Crokett's network, one name that jumped to the top is Randall Taylor. In the graph above, Taylor is the big red dot, with lots of little dots clustering around him. The big green dot is Richard Bentley, slightly more distantly connected to Crokatt, but also with a very high degree of betweenness, as is clearly indicated by the size of the node. (Click here for the live version of the 1692 network map.)

I would propose that "betweenness" could be connected to "Halloweenness." That is, if we want to know why our children say "boo" today, and not "bo," these nodes are both important – because they helped make the Scotch Presbyterian Eloquence what we might call a "viral" work, republished dozens of times, and read by everyone from Samuel Pepys to Jonathan Swift, who both owned copies. While Crokatt himself was a curate of a church in London and is basically unknown today, Taylor was one of the first "trade publishers," specializing mostly in publishing works in support of the government, an unofficial part of Roger L'Estrange's propaganda machine. When we run network analysis, we find that Crokatt is also connected to Richard Baldwin – another of the new breed of "publishers" remaking the industry, while Richard Bentley was among the most successful booksellers of his era. Known as "Novel Bentley" because of his specialization in early novels, Bentley held an interest in many important literary works, from Shakespeare to Milton.

And now for that note of caution. In running this analysis, we also generated some distinctly weird results, which could perhaps appropriately be summed up by the phrase "double, double, toil and trouble." First the doubles: alongside Taylor, Bentley, and the others, Charisse's data analysis for example produced very high betweenness results for "J. Johnson." In fact this was our top result. But that is because so many printers and publishers, for such a long stretch of time, were identified by this common name – and our data extraction technique has not yet differentiated them. We have J. Johnsons who were active in the early 1600s, the late 1600s, and all the way up to the 1780s. Clearly these are not all the same person, and one of our next tasks will be able to differentiate them using date and location limitations. The other problem is that Shakeosphere did not originally pick up Crokatt's own double, the pseudonymous "Jacob Curate." And in that trouble lies the toil: we will need to find a way to associate pseudonyms more firmly with authoritative author IDs, but for the time being it still takes a human reader to sort out this ambiguity.

Mon May 13 22:21:01 CDT 2024